Historical Mysteries of the Tai Tam Tuk Reservoir Dam

The Great Dam, The Great People

A chance spotting of some partly submerged constructions in Tai Tam Harbour led Dr Sun-wah Poon and Dr Katherine Deng of the Department of Real Estate and Construction to a series of fascinating archeological discoveries and evidence of historical engineering techniques. The discoveries, under the title “Commemorating the Centenary of Tai Tam Tuk Reservoir Dam on the Hong Kong Island – A Showcase of Interdisciplinary Archeological Evidence”, fanned community interest and awareness in Tai Tam Tuk Reservoir Dam and its history, and resulted in a string of well-attended talks, lectures and tours of the reservoir.

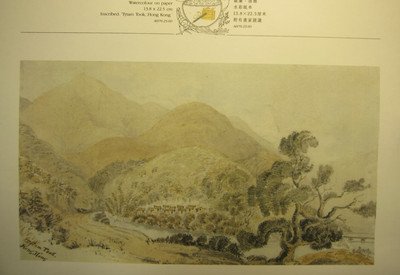

The Dam was completed in 1918, and at the time was the largest dam anywhere in the British Commonwealth. More than 100 years later, the Tai Tam Tuk Reservoir still plays a major part in Hong Kong’s water supply system.

The mysterious constructions turned out to be six wells, professionally termed as caissons, made of bricks and mortar. More than a century old, they are the only surviving evidence showing how ground investigation was carried out for reservoirs such as the Tai Tam Tuk reservoir. Contrary to normal practice with exploratory wells of this type, and for reasons unknown, the wells had not been filled in. They were found to have a depth of about 20 metres and had been built by hand.

The discoveries show that 120 years ago, the importance of security was taken as seriously as it is today. “They are clear evidence of the good investigation process 100 years ago,” said Dr Deng. “Their decision and conclusion is the same that we’re using currently,” noted Dr Poon.

Submerged in the reservoir Dr Poon found the remains of infrastructure works next to a tiny village dating from around 1845 once known as Tytam Took and nearby, almost covered by vegetation, the remains of the old site office and workers’ quarters, where about 400 workers once lived.

The dam is located in a beautiful setting popular with hikers, yet many had visited the site without knowing the story of the dam and its construction. As part of the dam’s centenary celebrations last year, Dr Poon and Dr Deng organised an exhibition in the HKU Main Library in February and March that showcased the team’s archeological evidence. The exhibition was extended to accommodate strong public interest and was attended by more than 1,000 visitors. The show helped the public learn more about Hong Kong’s built heritage and connect with the site’s social history, with one visitor mentioning that her father had worked in construction of the dam.

In addition to the exhibition, public lectures and guided tours at Tai Tam Tuk Reservoir were organised for professional groups, NGOs, secondary school teachers and students, and the general public.

The team’s archives, including photos, drawings, newspaper clippings, and artefacts found at Tai Tam Tuk, were also presented to the Water Supplies Department and the Antiquities and Monuments Office to enrich their exhibits of the Tai Tam Waterworks Heritage Trail.